586 KIA in Americas first battle to stop the Japanese Imperial Forces from invading Australia.

So I find a photo of the Company F, 127th Infantry as I recall from memory, 3 foot long to fit the entirety of members, and bring it to Dad with a “which one is you?” “You tell me” was his response. So I set about scouring the photo, “this one” — “nope,” “this one” — “nope” and on it went. I would put the photo away and drag it out every few months, “nope, no not me,” frustratingly put away and dragged out again in a few months, now a challenge to find dad. Given dads propensity to practical jokes I should have suspected something was up. The last I took it out he offered a clue.

When I last rolled it out on the dining room table with him I looked at him and said, “I think I’ve exhausted every person who closely resembles you.” “You know,” he said calmly as if in deep thought, of all the people in that photo only four made it to the end of the war without being seriously wounded or killed.” And it occurred to me that what I looked at as a historical photo to him was a remembrance of the hardships faced by the infantry in WWII. I put the photo back in the attic box determined not to be the trigger of memories not forgotten but kept below the surface lest they overwhelm.

Dad, like most WWII combat veterans, never talked much of his WWII experiences, especially in historical terms. He was a replacement for the casualties that occurred in his Division before his arrival. The three month boat ride to Australia, boredom, nothing to read but the bible or dictionary “and I learned a lot of words,” he said. Seasickness and guys puking, his favorite a guy heaving in a garbage can with his arms draped inside, too sick to get out and another guy loses it on the back of his head. As a replacement he was treated with aloofness “which was understandable as nobody wanted to get close to someone who might not live to see tomorrow and have to suffer their loss.” It was understood from the time of enlistment or draft that you were there until the end of the war or the end of you, maimed or dead.

He spoke highly of the “enemy,” especially the Imperial Marines he fought against. One of the few stories he related was in near hand to hand combat they were advancing, being repulsed, advancing and his buddy got mortally wounded as they were driven back. Advancing again he got to his buddy to find his feet had been cut off as they wanted his boots but didn’t have time to untie them. One could understand anger but I was presented with “Can you imagine how, if he lived, that poor guy suffered having to cut a guys legs off for a pair of boots.” The horrors of war are for all who suffer it.

Many years later I was in the process of donating my house to my future ex wife and sorting stuff I got out the photo and laid it flat with books, thinking to give it to my nephew. The photo disappeared in a fit of childish anger. At first I was angry as “my dads” photo was destroyed and then I remembered, “of all the people in that photo only four made it to the end of the war without being seriously wounded or killed.” The photo had to be of the 127th BEFORE they shipped out to war as you can’t be in a photo if you died in war and dad was a replacement for losses. Dad had sent me on the wild goose chase to find him and the joke was on me, and my ex also as the “photo of my dad” wasn’t and without him in it had little sentimental value to me.

Some years later I did a bit of research on the 32nd Red Arrow Brigade of which the 127th Infantry Battalion was one of 3 Brigades (https://www.32nd-division.org/history/). Of course the definitions in the Army change over time but generally the US Field Army is total soldiers, a Corp is 2+ Divisions, a Division is 3 Brigades, a Brigade is 3-5 Battalions, Battalion 3-5 Companies (from 100 to 1000 soldiers each), a Company is 3-4 Platoons (60-200 soldiers each), and a Platoon made up of Squads (6-10 soldiers). The 32nd Red Arrow Brigade was made up of 3 Battalions of multiple companies but understand much of the organization was being done on the fly.

The 32nd Red Arrow Infantry Division was formed from Army National Guard Units in Wisconsin and Michigan. In June 1940 Congress authorized inducting 18 National Guard Divisions for one year and training began in earnest as France had fallen and our participation was expected at some point. In August of 1941 Congress authorized the Selective Service Extension Act extending service for forever if necessary thus the “weekend warriors” (undermanned and ill equipped) were the first draftees. The 32nd was being prepared for duty in the US south and east for the European Theater where they distinguished themselves in WWI.

After the attack on Pearl Harbor the Japanese were making headway in the Pacific Island campaign and Australia was in danger of being invaded and was calling for their troops to return home from other theaters. Japan was on Papua New Guinea and supply lines to Australia were in danger of being cut off if they managed to take Port Moresby on the on the southeast coast of Papua (also Tulagi Island in the Solomon Islands endangered supply lines, both being resupplied and reinforced by Rabaul on the island of New Britain). The 32nd was reassigned to support in the Pacific Theater and transported from the east of the US to the West Coast (given 3 weeks to get to the west coast, a US Army hurry up and wait cluster f**). Transported by ship, in Australia and untrained for jungle warfare they began minimally training for such as their initial assignment was defense of Australia.

Japan was determined to take Port Moresby by sea but in the Battle of the Coral Sea 4-8 May 1942 (the first where neither opposing fleet saw nor fired on the other, relying solely on air power) scuttled their plans. The Battle was a stalemate with both naval sides losing assets (US Fleet Carrier Lexington sunk, a destroyer and Fleet Carrier Yorktown returning to Hawaii for repairs and Japan losing one light carrier, one destroyer, and one fleet carrier damaged in addition to planes). While the loss to the Americans was worse it stopped the invasion of Port Moresby due to the loss of air cover and the Japanese scuttled the plans to invade Port Moresby by sea.

Undaunted the Japanese landed at Gona on the Northeast Coast of Papua and looked to traverse the Kokoda Trail to take Port Moresby. The Japanese made it to within 20 miles of Port Moresby, held in check with fierce fighting from Australian Troops. Guadalcanal was taken by the Japanese to build an air strip to facilitate the taking of Port Moresby and eventually Australia. Both resupplied by Rabaul advances on one front aided the other.

The US dual front of Gen. MacArthur and the US Army into Papua and then the Philippines and Admiral Nimitz and US Marines through the Solomon Islands and then Guam was beginning. First the Battle of Midway (4-7 June 1942) decimated the Japanese Navy and then the assault on Guadalcanal (begun 7 August 1942) in the Solomon’s had Japan’s leaders decide to retreat in Papua to Buna-Gona and abandon the assault on Port Moresby for the time being. The Japanese war strategy (unknown to the Americas) was to wait to see how Guadalcanal went.

Lacking naval support due to the Battle of Guadualcanal MacArthur agreed to use the Air force for transport to Port Moresby, the first ever air transport of troops en mass. Mac Arthur ordered troops over the Kapa Kapa Trail (Ghost Mountain) over the Owen Stanley Range to secure the flank of the Australians but the ill planned adventure was not a failure to the fact that the Japanese were in tactical retreat to Buna-Gona. The Ghost Mountain Boys by James Campbell tells that story. The troops passing over that trail were so decimated by conditions none were sent by that root again.

Buna was MacArthurs first offensive. With a 3 ft. water table there was no digging in but Japanese fortifications were built above ground with coconut log bunkers. The MacArthur offensive lacked sufficient bunker busting artillery and the little they did have was bogged down in the swamps. The troops had little jungle training and started to offensive at the beginning of the rainy season with daily downpours of up to 10 inches of rain common. They lacked machetes and waterproof containers nor any specialized jungle warfare gear.

The Japanese were well protected by fortifications many connected by trenches with supporting lines of fire at Buna and manned by battle hardened troops. The assault began on 16 November 1942 and was declared over 21 January 1943. In December 1942 Time Magazine reported “Nowhere in the world today are American Soldiers engaged in fighting so desperate, merciless, so bitter, or so bloody.” As bad as the Australians and Americans had it the Japanese had it worse with many resorting to cannibalism of their own and enemy KIA. “If they don’t stink, stick ‘em” was the motto as the Japanese would not surrender and many feigned death to lure Americans in close for a suicide attack. It was win or lose no surrender warfare.

Ill prepared and lacking training and equipment the 32nd suffered 2520 casualties of 9825 men, 586 KIA, 66% of the diseased malarial, denge fever, etc. population causing the 9956 casualty count to exceeded the Divisions Battle strength. The “Ghost Mountain” boys had 126 standing out of 900 plus sent on the mission. The 32nd ended the battle with under 800 men fit for combat duty. As men will do, minimize men’s suffering by pointing to those who suffer worse, the marines in the hospital from Guadalcanal said, “at least I didn’t suffer Buna.”

1 March 1943 the decimated 32nd Red Arrow was sent back to Australia for refit and to be retrained. Many of their tactical experiences were used to train American and Australian soldiers for jungle warfare

History remembers Guadalcanal and Midway but it was the Battle of the Coral Sea where the US Navy first stood against the Japanese advance in the Pacific and stopped it and it was the Papua, New Guinea and the Battle of Buna where the Imperial marines were stopped in their advance by American and Australian Infantry. The fight for New Guinea was the forgotten war in the Pacific where poorly trained and equipped American Infantry learned how to, and that they could, fight and win.

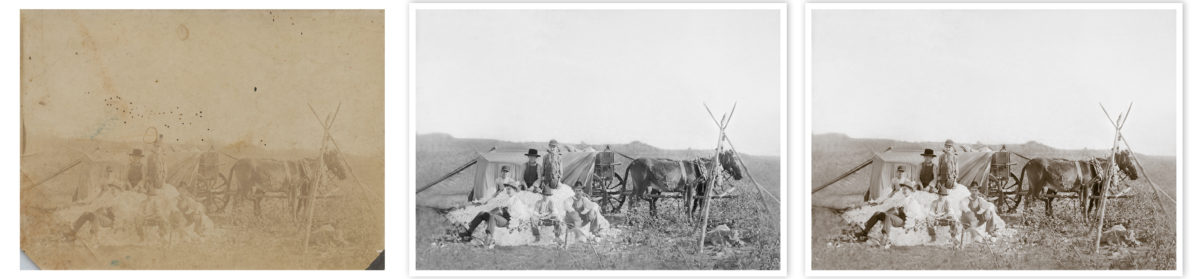

Photos (excepting photo’s of James H. Hays copywrite by AmericanMan.org) reproduced from the 32nd Red Arrow Division web site under fair use doctrine and copying from this site is neither denial or approval for use.

Further reading: 32nd Red Arrow Division at https://www.32nd-division.org

Time in Hell: The Battle for Buna on the Island of New Guinea, The story of Company F, 127th Infantry Division Wisconsin National Guard, Sheboygan, Wisconsin by Richard A. Stoelb 2012 Sheboyan County Historical Research Center

The Ghost Mountain Boys by James Campbell 2007 Three Rivers Press.

The Honor of His Service: The Life of a 32nd Infantry Division Service member During World War II by Rodger Woltjier, Colonel Retired 2012 Marriam Press