The Big Y Test Reveals a common Hays ancestor in 1550 CE for Patrick Hays (1720s PA) and John Hays (1740s VA) and a distinct DNA line for Patrick Hays (PA).

Four of us Ulster Scot Hays whose ancestors migrated to the America’s in the early 1700s have completed the Big Y 700 at Family Tree DNA and have family trees going back to either Patrick Hays settling in Derry, PA 1728 or John Hays settling in Augusta, VA in 1740. DNA indicates that both have a common ancestry from Ulster, Ireland. With a mutation from a common ancestor in 1550 and a second mutation in 1750. Persons with the “Hays” surname and lacking recorded evidence of ancestry may be able to use the Big Y DNA test to identify their line back to Scotland through Northern Ireland and the pioneer settlers in PA and VA in America in the 1720s and 1740s respectively.

If I’m reading this correctly, our common ancestor is R-FT115175. He was in 1550 CE (1296-1706) the parent group from which R-FT115690 mutated from. R-FT115690 is the parent of R-FT116536 which mutated in 1750 CE (1657-1857). We have 2 persons with R-FT116536 and they trace to Patrick Hays 1705-1790 in PA. We have 2 persons with R-FT116590 who trace their ancestry (highly suspected) to John Hays 1674-1750 in VA. Thus any person doing research on their Hays line who matches an ancestor in the line of the 4 listed can be reasonably certain (barring any errors in the genealogy trees) that they are from the Patrick Hays or John Hays lines. The R-FT116590 shows relations to John Hays from the mutation in 1550 which may be a relative 175 years before his birth. The R-FT116536 mutation may be Patrick Hays himself or his father or grandfather and as such relation may be through his brothers, or an unknown cousin, who migrated with him in the early 1700s.

R-FT116590 and R-FT116536 family trees: (As reported by the individuals, Patrick or John into the 1800s).

- R-FT116536 Patrick Hays 1705-1790, Samuel Hays ? Dauphin County, PA – 1805 Warren, Kentucky, William Hays 10 Mar 1761 Augusta, VA – 25 Sep 1851 Warren Kentucky, Daniel Hays 1799 ? – 1862 Warren, KY.

- R-FT116536 Patrick Hays 1705-1790, Samuel Hays 1741 Dauphin County, PA 1805 Bowling Green, KY, James Hays 1758 Augusta, VA (1783 lived in Davidson, TN) – 1830 Warren County, KY, John Hays 1785 Lincoln County, KY – ?, James Samuel Hays 1822 Bowling Green, KY – 1860 Marlin, TX.

- R-FT116590 John Hays (unconfirmed) 1720 Bangor, Ireland – ? Augusta, VA, Unknown Hays, William Hays 1753 VA – 1831 Wythe, VA, Jacob Hays 1785 Rich Valley, Montgomery, VA – 1858 Brunswick, MO

- R-FT116590 (me) John Hays 1674-1750, James Hays unk (Ulster)-unk, James Hays unk-unk, William Hays 3 Mar 1773 Rockbridge, VA – 10 Sep 1857 Greene, TN, George Hays 1802 Blue Springs, Greene, TN – 1866 Blue Springs, Greene, TN, William A. Hays 1835 Clear Creek, Greene, TN – 1911 Cedar Lane, Greene, TN.

At Family Tree DNA, the 67 Marker YDNA has 2 persons with a genetic distance of 3 steps from me, one traced back to Patrick Hays and one traced back to John Hays. FTDNA advises that at 111 markers 0 steps removed is accurate to 6 generations, 1 step is 9 generations, and 2 steps are 11 generations. At 111 there are 2 persons 5 steps removed with 1 tracing to John Hays and 1 tracing to Patrick Hays and one 6 steps removed tracing to Patrick Hays. The 67 and 37 marker tests show the Y-DNA Haplogroup R-M269 which mutated 4000 years ago (with 14 mutations to R-FT115175) thus any Y-DNA test below the Big-Y 700 will not provide any help in determining which Hays line you came from given he common ancestor R-FT115175 in 1550 Scotland and the common ancestor branches from R-FT116590 in late 1600-early 1700s Ulster Ireland.

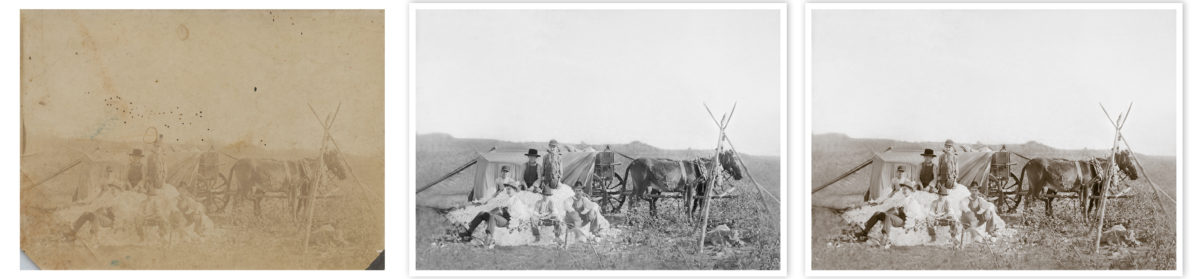

These Hays arrived, most likely, in Philadelphia settled on the edge of the European settlements between existing original settlers and the natives (which we will discuss further in later blogs). There were scant written records when the Hays arrived in America and the European settlements didn’t venture far inland from the coastal settlements. As an example Patrick Hays settlement in Dauphin County in 1728 was well beyond the “Walking Purchase” of land from the Lenape (Delaware) Indians in 1737. The settlement in the Shenandoah River Valley of Virginia of John Hays in the 1740s likewise was intended to provide a buffer between the original settlers in Jamestown and the natives, luckily recorded in the Lyman Chalkley “Chronicles of the Scotch-Irish Settlement of Virginia.”

By 1700 the powerful Iroquois Federation (originally 5 tribes: Mohawk, Oneida, Onondaga, Cayuga, and Seneca adding a 6th, the Tuscarora in 1722) controlled most of present day NY, PA, VA and the lands west to the Ohio River Valley and beyond (control claimed by other tribes also). The 1722 Treaty of Albany (NY) was supposed to stop settlement beyond the Blue Ridge Mountains at the Great Warriors Path (southeast of the Appalachian Mountains) but the number of settlers outpaced available land and settlement continued west in PA and then southwest following the Shenandoah Valley. In 1742 a party of Onondaga and Oneida Indians skirmished with the Augusta, VA Militia and in 1744 at the Treaty of Lancaster the Iroquois sold the Shenandoah Valley which increased settlements and development of the Great Wagon Road (former Great Warriors Path) which stretched from Philadelphia to Gettysburg then southwest to Roanoke and then south into the Piedmont of North Carolina and continuing through South Carolina ending at Augusta, GA on the Savannah River.

The Biographical Encyclopedia of Dauphin County PA states that Patrick Hays was born in Donegal, Ireland in 1705 and arrived in PA settling in Dauphin County, Derry, PA in 1728 with his brothers, Hugh, William, and James. Patrick had 5 sons (David, Robert, William, Samuel, and Patrick). James is presumed dead by 1751 and brother Hugh and William travel to Virginia in the early 1750s with Hugh returning to PA until his death with only a daughter recorded. Patricks 2 sons, William (b. 1737) and Samuel (b. 1741) also travel to Virginia.

John Hays and Patrick Hays (VA) self imported to Orange County, Virginia in 1740 from Northern Ireland via Philadelphia (unknown arrival year). As self importers they were entitled to settle land which was awarded in two grants, one the Beverly Grant and the other the Borden Grant (which we will explore in depth in a future blog). Patrick settled with his wife Frances and children Joan, William, Margaret, Catherine, and Ruth. John’s wife was Rebecca with children Charles, Andrew, Barbara, Joan, and Robert.

Patrick’s (PA) brothers Hugh and William travelled to Virginia in the 1750s and his sons William (1737) married (1767 ) Jean Taylor and Samuel (1741) married unknown and removed to Virginia also. It is possible they continued down the road into North Carolina also given the Indian hostilities occurring at the time. The French and Indian War, 1754-1763 caused much movement between Virginia, Pennsylvania, and North Carolina which ended with the treaty of Paris with England controlling the Ohio Country. In 1763 a Royal Proclamation was issued preventing settlement past the Appalachian Mountains to try to prevent conflict with the Indians.

Thus, due to a hostile frontier, and until the end of the Revolutionary War 1775-1873, settlement was restricted and movement amongst the Hays ancestors of Patrick and John Hays occurred mostly in Pennsylvania, Virginia, and North Carolina with many moving back and forth as hostilities moved about. Excursions into Kentucky began with Daniel Boone and his son in law Capt. William B. Hays cutting the Wilderness Road through the Cumberland Gap and the Wautauga Settlement on leased land from the Cherokee in East Tennessee but widespread settlement wasn’t to occur until the end of the war. Virginia (who controlled Kentucky) ceded their wilderness land to the Federal Government in 1783 and North Carolina (which controlled Tennessee) started land grants and then ceded their wilderness lands to the Federal Government in 1790. Many of our Hays ancestors continued their pioneering with land grants in TN and KY.